Have you ever been walking along and felt the creepy, unsettling feeling that something was watching you? You may have met Betobeto-san, an invisible yōkai, or folklore creature, who follows along behind people on paths and roads, especially at night. To get rid of the creepy feeling, simply step aside and say, “Betobeto-san, please, go on ahead,” and he will politely go on his way.

What we know of Betobeto-san and hundreds of other fantastic creatures of Japan’s folklore tradition, we know largely thanks to the anthropological efforts of historian, biographer and folklorist, Shigeru Mizuki, one of the pillars of Japan’s post-WWII manga boom. A magnificent storyteller, Mizuki recorded, for the first time, hundreds of tales of ghosts and demons from Japan’s endangered rural folklore tradition, and with them one very special tale: his own experience of growing up in Japan in the 1920s through 1940s, when parades of water sprites and sparkling fox spirits gave way to parades of tanks and warships.

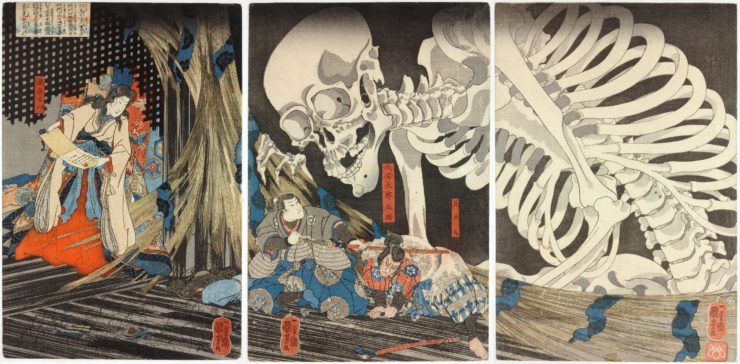

Trickster-fox Kitsune, dangerous water-dwelling Kappa, playful raccoon-like Tanuki, and savage horned Oni are only the most famous of Japan’s vast menagerie of folklore monsters, whose more obscure characters range from the beautiful tentacle-haired Futakuchi Onna, to Tsukumogami, household objects like umbrellas and sandals that come alive on their 100th birthdays, and tease their owners by hopping away in time of need. Such yōkai stories have their roots in Japan’s unique religious background, whose hybrid of Buddhism with Shinto animism adds a unique moral and storytelling logic to these tales, present in no other folklore tradition, whose twists and turns—unexpected within Western horror conventions—are much of why fans of the weird, creepy and horrific find such extraordinary power in the creations of Japan. Most accounts of yōkai and Japanese ghosts are regional tales passed down at festivals and storytelling events in rural parts of Japan—and, like many oral traditions, they dwindled substantially over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the rise of cities, and of centralized and city-dominated entertainments provided by cheap printing, radio, film and television.

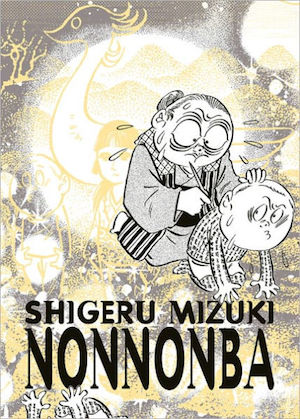

Shigeru Mizuki spent decades collecting these stories from all corners of Japan, and setting them down in comic book form, so they could be shared and enjoyed by children and parents across Japan and around the world, as he had enjoyed them in his childhood. While most of Japan’s 20th century manga masters had urban roots, Mizuki grew up in the small, coastal town of Sakaiminato, delighting in local legends told to him by a woman he describes in the memoir he titled after her, Nononba (the first Japanese work ever to win grand prize at the world famous Angoulême International Comics Festival.) Mizuki’s father was deeply interested in international culture, especially film, and even acquired the town’s first movie projector, hoping to connect his family and neighbors to the new arena of the silver screen. This childhood exposure to both local and global storytelling cultures combined to make him eager to present the wealth of Japan’s folklore on the world stage.

Mizuki’s most beloved work Hakaba Kitaro (Graveyard Kitaro, also called GeGeGe no Kitaro) debuted in 1960, and follows the morbid but adorable zombie-like Kitaro, last survivor of a race of undead beings, who travels Japan accompanied by yōkai friends and the talking eyeball of his dead father. In different towns and villages, Kitaro meets humans who have run-ins with Japan’s spirits, ghosts and underworld creatures. Sometimes Kitaro helps the humans, but he often helps the spirits, or just sits back to watch and mock the humans’ ignorance of the netherworld with his signature creepy laugh “Ge… ge… ge…” Kitaro’s adventures also chronicle the social history of 20th century Japan, as the yōkai themselves struggle to adapt to cultural changes and economic doldrums, which lead to the closing of shrines, dwindling of offerings, and destruction of supernatural habitat. Adapted into dozens of animated series, movies and games, the popularity of Kitaro made yōkai tales a major genre, but Shigeru Mizuki’s signature remained his commitment to chronicling the rarest and most obscure stories of Japan’s remote villages, from the Oboroguruma, a living ox-cart with a monstrous face, reported in the town of Kamo near Kyoto, to the thundering Hizama spirit of the remote island of Okinoerabu. In fact, when a new animated movie of Kitaro was released in 2008, it screened in six different versions to feature the local folklore creatures of different regions of Japan. In addition to Hakaba Kitaro, Mizuki wrote books on folklore, and encyclopedias of Japanese ghosts and yōkai.

Mizuki was also one of the most vivid chroniclers—and fiery critics—of the great trauma of Japan’s 20th century, the Second World War. Drafted into the imperial army in 1942, Mizuki experienced the worst of the Pacific front. His memoir Onward Toward Our Noble Deaths (whose English translation won a 2012 Eisner award) describes his experience: unwilling soldiers, starving and disease-ridden, sent on suicide runs by officers who punished even slight reluctance with vicious beatings. In fact Mizuki’s entire squad was ordered on a suicide march with explicitly no purpose except honorable death. Mizuki alone survived, but lost his arm, gaining in return a lifelong commitment to further the cause of peace and international cooperation. In earlier works—published when criticism of war was still unwelcome and dangerous in Japan—Mizuki voiced his critique obliquely, through depictions of Japan’s economic degeneration, and through his folklore creatures, which, in his tales, are only visible in times of peace, and are driven out and starved by war and violent hearts. Later he wrote more freely, battling historical revisionism and attempts to valorize the war, through works like his biography Adolph Hitler (now in English), and the unforgettable War and Japan, published in 1991 in the educational youth magazine The Sixth Grader, which confronted its young readers the realities of atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese army in China and Korea.

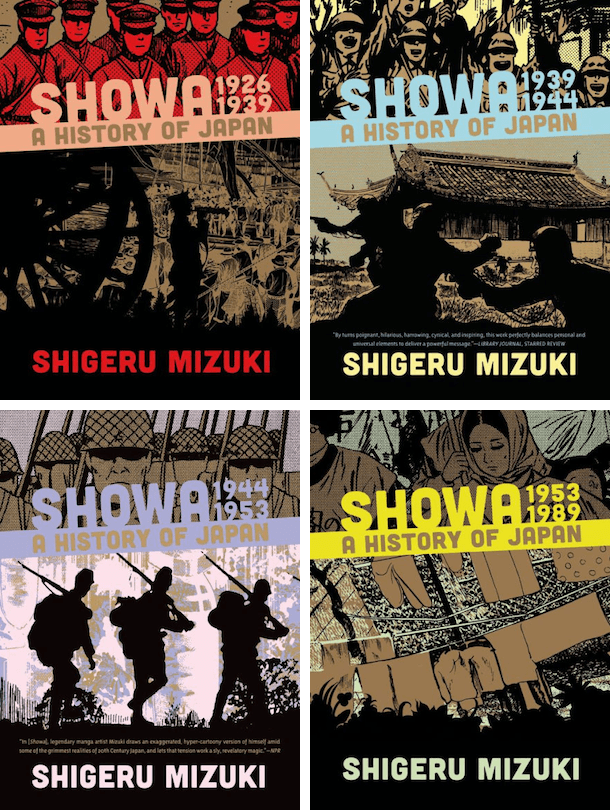

Mizuki’s magnificent 1988-9 history Showa (recently released in English translation) is a meticulous chronicle of Japanese culture and politics in the decades leading to and through the war. It shows the baby steps of a nation’s self-betrayal, how nationalism, cultural anxiety, partisan interests, and crisis-based fear-mongering caused Japan to make a hundred tiny decisions, each reasonable-seeming in the moment, which added up over time to a poisonous militarism which saturated the culture from the highest political circles all the way down to children’s schoolyard games. Its release in English is absolutely timely. If the dystopias which have so dominated recent media are tools for discussing the bad sides of our present, doomsday ‘what if’ scenarios where our social evils are cranked up to a hundred, Showa is the birth process of a real dystopia, the meticulously-researched step-by-step of how social evils did crank up to a hundred in real life, and the how the consequences wracked the world. Phrases like “slippery slope” are easy to apply in retrospect, but Showa paints the on-the-ground experience of being in the middle of the process of a nation going mad, making it possible to look with new, informed eyes at our present crisis and the small steps our peoples and governments are taking.

Shigeru Mizuki’s contributions to art, culture and humanitarianism have been recognized around the world, by the Kodansha Manga Award and Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize, the Eisner Award and Angoulême festival, the Japanese Minister of Education award, Person of Cultural Merit award, and a special exhibit of his work for the 1995 Annual Tokyo Peace Day. His works have long been available in French, Italian and many other languages, but, despite Mizuki’s eager engagement with English-speaking fans and his eagerness to share his message with the world’s vast English-reading audiences, his works were slow to come out in English because his old-fashioned “cartoony” art style—much like that of his peer and fellow peace advocate “God of Comics” Osamu Tezuka—does not fit the tastes of American fans, accustomed to the later, flashier styles of contemporary anime. In Mizuki’s last years, thanks to the dedicated efforts of Montreal-based publisher Drawn and Quarterly, he finally oversaw the long-awaited English language release of his memoirs and histories, along with the Kitaro series (more volumes still coming out), which Drawn and Quarterly aptly describes as “the single most important manga you’ve never heard of, even if you happen to be a manga fan.”

One of Japan’s most delightful folklore traditions is Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, a gathering of one hundred supernatural stories. A hundred candles are lit, and participants stay up all night telling tales of ghosts and spirits, extinguishing one candle at the end of each tale, so the room grows darker and darker, and the spirits—attracted by the invocation of their stories—draw near. A Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai is rarely finished, since few gatherings can supply a full hundred stories, and, as the dark draws in, most participants grow too frightened to snuff the last candle. But the millions touched by works of Shigeru Mizuki are well prepared to finish, armed with well over 100 stories, and with a powerful sense of the vigilance and hard work necessary if we want to welcome peaceful yōkai back to a more peaceful world.

This article was originally published in December 2015 in remembrance of Shigeru Mizuki.

Ada Palmer is the author of the Terra Ignota series—Too Like the Lightning, Seven Surrenders, and The Will to Battle. She is a historian, working primarily on the Renaissance, Italy, and the history of philosophy, science, books and printing, heresy, and freethought, as well as manga, anime and Japanese pop culture. She writes the blog ExUrbe.com, and composes SF & Mythology-themed music for the a cappella group Sassafrass.

Thanks for this. Will certainly check out Kitaro.

And thanks for Too Like the Lightning.

Andrew, who did a TLtL timeline.

Great read! Really enjoying the volumes of Kitaro D&Q is publishing, hopefully we get an English translation of “War and Japan” in the near future.

Like many westerners, my introduction to yōkai tales was Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan. Sure, it’s dated and he confuses a noppera-bō with a mujina, but it’s a good read. There’s a great yōkai database out there, which is beautifully illustrated.

Funny, I had just started an Inuyasha-watching binge this week, so yōkai have been on my mind lately.

My introduction to yokai tales was the movie Kwaidan, which in turn introduced me to the book it was based on. A strange paradox this, a Japanese movie based in a book by a gaijin who made his life work to compile Japanese tales. A para-paradox, if you will.

It is a strange thing to call Hearn’s book “dated,” though. We might as well call Dickens “dated.”

Dear preceptor of speculative histories

if Ada Palmer were to go and write a Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai (even a little one!), I would seize it with glee, and keep it safe on my bookshelf forever.

very cool